Pugilist friends may tend toward “hard” fighting styles like boxing or karate, and the fearful in our midst may gird themselves with concealed pistols, but thoughtful people recognize that they have far more to fear from stress and the degenerative diseases of aging than from parking-lot villains. While so-called internal martial arts (tai chi, bagua, hsing-i, etc.) are indeed deadly and effective, they are most valuable to us these days in that they are a path to wu wei.

A famous Taoist concept, wu wei, is often construed as inaction. It would be more accurate to think of it as restrained and maximally efficient action, or, perhaps, simply going with the flow. In China, where the individual was traditionally valued most for what he or she contributed to the community, the efficient, conservative use of energy and resources was the preferred modus operandi. Wu wei, therefore, connoted being supportive of, and in tune with, the world around us. In the west, however, wu wei has been associated with such tactics as offering no overt resistance, rarely initiating movement, keeping a low profile, and refraining from making waves. Since Western culture emphasizes the illusion of personal control and is more likely to reward the squeaky wheel than the quiet one, wu wei may smack of an undesirable tendency to let our lives control us rather than the other way around.

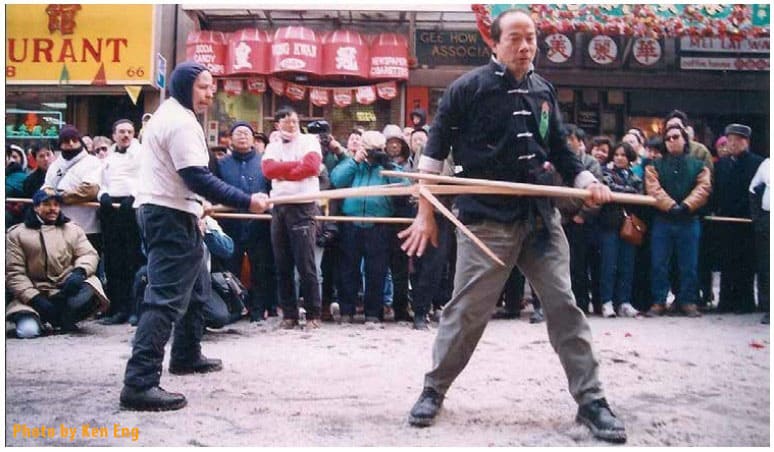

This latter preference  widely carries over to our Western choices of martial arts styles. Geared toward confrontation and tests of strength and skill, depending upon the reassurance of feeling force against force, many of us gravitate towards more overtly confrontational fighting styles such as Mixed Martial Arts, Sistema, Krav Maga, karate, Escrima, or boxing, and associate internal martial styles with health benefits rather than combat effectiveness. Construing going with the flow as being passive or lazy, softness as being weak, and an internal orientation as narcissistic, we may even see internal arts that cultivate wu wei as best suited to elderly people seeking longevity and community.

widely carries over to our Western choices of martial arts styles. Geared toward confrontation and tests of strength and skill, depending upon the reassurance of feeling force against force, many of us gravitate towards more overtly confrontational fighting styles such as Mixed Martial Arts, Sistema, Krav Maga, karate, Escrima, or boxing, and associate internal martial styles with health benefits rather than combat effectiveness. Construing going with the flow as being passive or lazy, softness as being weak, and an internal orientation as narcissistic, we may even see internal arts that cultivate wu wei as best suited to elderly people seeking longevity and community.

Martially speaking, going with the flow means avoiding meeting force with force, and suggests using an opponent’s energy against him or her. The tai chi ch’uan classics tell us that to match brawn with brawn is to risk defeat, as we cannot always count on being stronger than our opponent. Instead, these same classics (texts and their attendant commentaries, some of them very ancient) advise us to relax and employ the various techniques of our internal training—foremost among which are sensitivity, spiral motion, rooting skills, and speed—to use an opponent’s energy against him. All of this requires a great deal of introspection, the cultivation of a calm mind, the repeated training of a relaxed response, and consistent attention to our foibles, habits, and limitations, all of which combine to present us with work that is often more challenging than simple physical training.

This pursuit of wu wei (and I use the term pursuit advisedly, as we don’t really pursue such an effortless quality so much as we allow it to arise) proves to be fascinating enough to compel many of us into a lifetime of study. It is variously brutally effective, frustratingly difficult, seductively fascinating, or seemingly unattainable. Yet the clarity of self, the deep and salutary insights, and the calmness of spirit internal arts require eventually lead to measurable and gritty mental and physical pay-offs. By learning to meet an incoming fist or foot without panicking, we are learning the hardest lesson first. If we can achieve profound relaxation during our martial practice, we can face the rest of the curve balls that life throws our way with centered serenity. If we can overcome the surge of combat adrenaline, the tense, angry, fearful fight-or-flight response, we can respond to with equanimity and strength to angry bosses, upset children, difficult family members, needy friends, and calamitous turns of fate. In much the same way a sports car designed for 180 mph is a rock-stable joy to drive at 65, the internal artist who has found wu wei will experience an unfolding degree of satisfaction, effectiveness, and effortless success that are among life’s greatest achievements.

-Monk Yunrou

More insights from Yunrou are found in his novel, YIN.

It is a work of magical realism in the vein of Gabriel Garcia Márquez and David Mitchell, YIN chronicles the efforts of the great sage to create the woman of his dreams. It is a novel of idealism, frustration, persistence, unimaginable endurance, failure, tragedy, and triumph.